There was a double feature playing a few nights ago, Laura and Bedelia, both based on books by Vera Caspary. I was so exhausted from the grueling Noir City Film Festival pace (four movies on Saturday) that I thought I’d skip the movie version of Laura (which I’ve seen more times than I can remember) and read the book instead.

Caspary wrote Laura in 1942, and the eponymous heroine is a curtain opener for the career girls who would later flood the fiction market. In 1943 the New York Times called this story of an advertising executive who is presumed murdered and then turns up alive and becomes a suspect “quite different from the run-of-the-mill detective story.” The book spends more time on Laura’s modernity as an “independent woman” and “bachelor girl” than the film does. Preminger followed the plot-line pretty closely (for all that he claimed that he made up everything but the basic premise himself) but he was uninterested in exploring the social problems of working women and favored the twisted relationships and necrophilia angle–all very titillating and good movie fun.

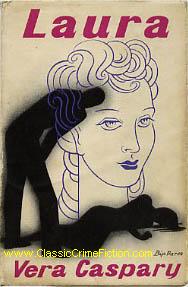

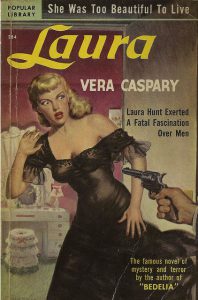

Laura cover 1950, with sex-appeal now added

Vera Caspary asked Preminger (after reading a first draft of the script) “Why don’t you give her the character she has in the book?” He said, “In the book, Laura has no character…Laura has no sex.” I guess it depends on your point of view.

In the book, Waldo tells us, much as he does in the movie, about Laura’s transformation from naive newcomer to sophisticated New Yorker, although in the book there’s more detail and again that slight change of emphasis that makes all the difference. We’re told Laura came from Colorado Springs when she was eighteen or nineteen possessed of a “magnificent will” and “willing to suffer endless rebuffs in order to prove her talents.”

In the movie, Laura says of her mother, “She listened to my dreams of a career and then taught me another recipe.” in the book, there are two mentions of Laura’s mother: Laura remembers her advice, “Never give yourself, Laura, never give yourself to a man” and recalls how her mother would lock herself in the bedroom with “a sick headache”–a hint, perhaps, as to why Laura was so eager to leave Colorado Springs.

In the movie, Laura is basically hoodwinked by Shelby Carpenter, the handsome southern cad on his way to becoming a gigolo whose ultimate destiny is Laura’s aunt, Ann Treadwell (Aunt Susie in the book). In the book, Laura thinks back on their relationship, two years of quarrels and reconciliations and reflects, “I had used him as women use men to complete the design of a full life….Going on thirty and unmarried I had become alarmed.”

In the movie, Laura excuses her weekend away by saying she needed to think. In the book, Caspary is at pains to explain that Laura’s weekend away by herself before her marriage to Shelby is the equivalent of a bachelor dinner, a last celebration of freedom before submitting to the matrimonial noose. “Owning myself, possessing all my silly and useless routines and being the sole mistress of my habits…freedom meant my privacy.”

Both movie and book do a lot of hinting at alternatives to the heterosexual pairing; hints that don’t always make sense in the context of the plot, except to add to the “sophisticated” ambiance (and believe me, if I could make something of the description of Bessie as “more than a maid to Laura” I would). In the book, Laura thinks of the “way we proud moderns have twisted and perverted love, making arguments for this and that substitute.” In both book and movie, Mark is positioned as successor to Laura, Waldo’s next protege, although it’s a lot clearer in the book. One of the lines the censors wanted cut from the movie is Mark telling Waldo, “You like your men better if they’re not a hundred percent,” which the censor said had “the unacceptable flavor of a possible pathological sex angle so far as Waldo is concerned.” Of course the movie has what is worth a thousand suggestive lines, the performance of Clifton Webb as Waldo Lydecker.

Which makes the whole plot unconvincing. Waldo is supposedly in love with Laura, and wants to kill her because he can’t bear the thought of her in another man’s arms. And yet in the early scenes of the movie, Waldo is practically courting Mark; Then, confusingly, he declares his love for Laura with his last breath at the film’s conclusion. It’s perhaps a case of Hollywood (and Caspary it must be said) not daring to take the titillating storyline they’ve created to its logical conclusion. The only way to make sense of this “psychothriller” as the publishers billed the book, is to suppose that Waldo’s admiration for Laura has a flip side–envy for her ability to attract men like Mark (and perhaps Shelby and Jacoby). Laura is the rival Waldo wants to eliminate, but due to a bad case of freudian transference-love-object-substitution…

Which makes the whole plot unconvincing. Waldo is supposedly in love with Laura, and wants to kill her because he can’t bear the thought of her in another man’s arms. And yet in the early scenes of the movie, Waldo is practically courting Mark; Then, confusingly, he declares his love for Laura with his last breath at the film’s conclusion. It’s perhaps a case of Hollywood (and Caspary it must be said) not daring to take the titillating storyline they’ve created to its logical conclusion. The only way to make sense of this “psychothriller” as the publishers billed the book, is to suppose that Waldo’s admiration for Laura has a flip side–envy for her ability to attract men like Mark (and perhaps Shelby and Jacoby). Laura is the rival Waldo wants to eliminate, but due to a bad case of freudian transference-love-object-substitution…

I did end up seeing Laura, the movie, at least the second half, after running across the street for a bite to eat. I made sure to get back in time to watch my favorite scene (not in the book), in which Judith Anderson as Ann Treadwell makes a speech about how she’s no good and Shelby’s no good and they belong together, all while looking in the mirror, adjusting her hat and redoing her lipstick. I love it in part because the first time I saw Laura, a matinee at Theatre 80 St. Marks in New York in the late eighties, the entire audience of primarily gay men burst into applause at the speech’s conclusion.

Further Reading: Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King, Foster Hirsch; The World and Its Double: The Life and Work of Otto Preminger Chris Fujiwara